On the Apple Silicon M1 MacBook Pro

2020-11-26I’ve been loving computers and computing since I was five years old, and in the intervening 25 years, I’ve never been more excited about anything in computing as much as I was about the Apple Silicon M1 chip when it was announced on November 10th. The M1 promised to bring huge leaps in performance, battery life and hardware longevity at a $999 price point and in a fanless chassis. It felt genuinely exciting to see such a significant leap in computing technology all at once.

The elements that stick out the most about why the M1 is special can be summarized as the following: a five nanometer process, an ARMv8-AArch64 instruction set, unified memory, separate performance and efficiency cores and a ton of accompanying hardware offering acceleration for video decoding, cryptographic operations and more. There’s also a bunch of dedicated silicon for GPU cores that have been shown to rival the Nvidia GTX 1060. This is all on an integrated SoC that consumes a maximum of 15 watts and that generally runs on far less. This is all in a context where Intel is shipping 45W and 65W processors inside laptops, built on 10-14nm transistors, with a dinosaur-age x64 instruction set and integrated graphics that are certainly not even close to competing with a dedicated GTX 1060.

Apple did something very annoying and very Apple by showing graphs such as this one at its unveiling event:

This graph is completely worthless. Honestly. Nobody knows to this day what Apple meant by “Latest PC laptop chip”, and both axes aren’t even numbered. It’s stupid that Apple still pulls this sort of thing off, and it immediately makes you question just how good the M1 is really supposed to be.

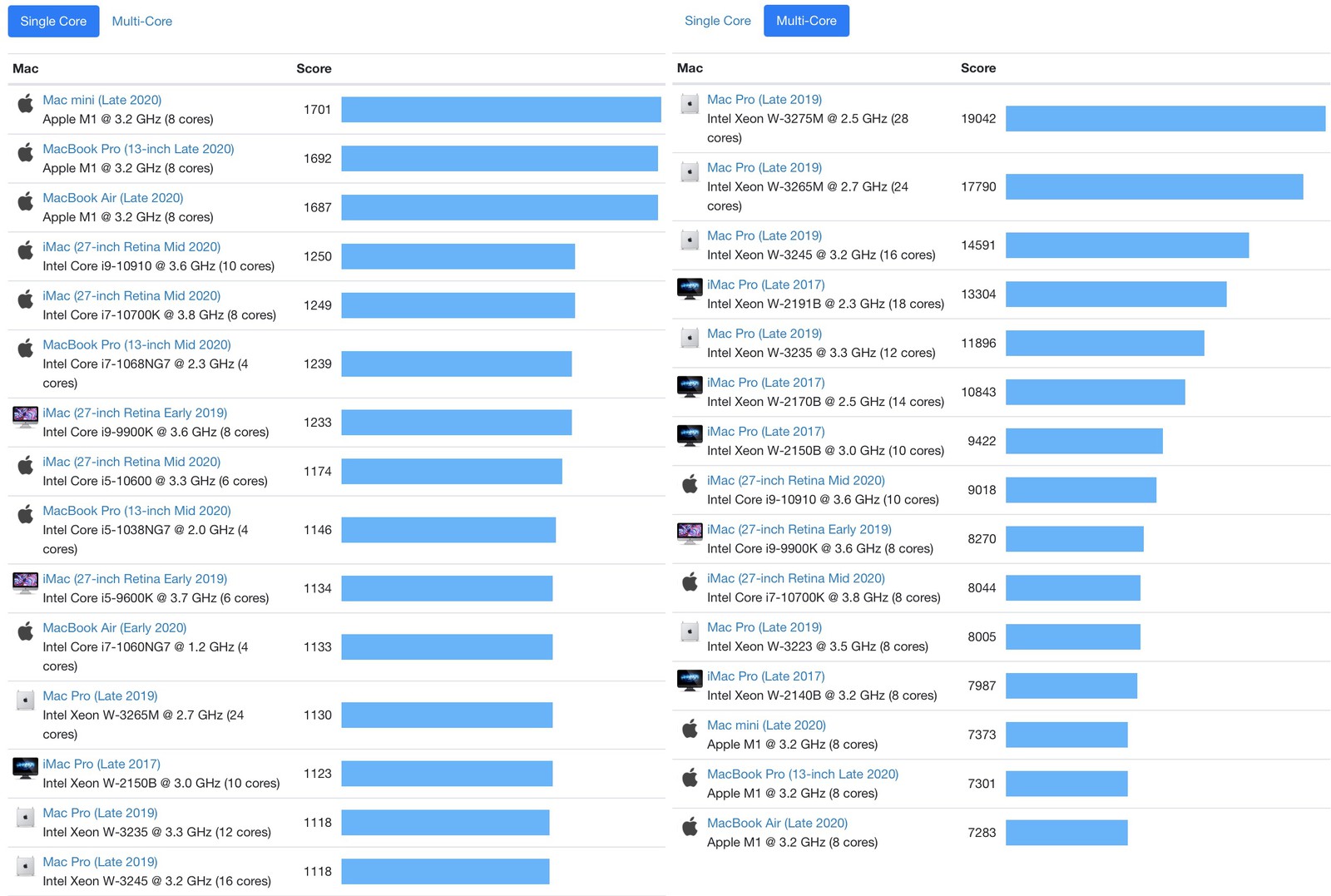

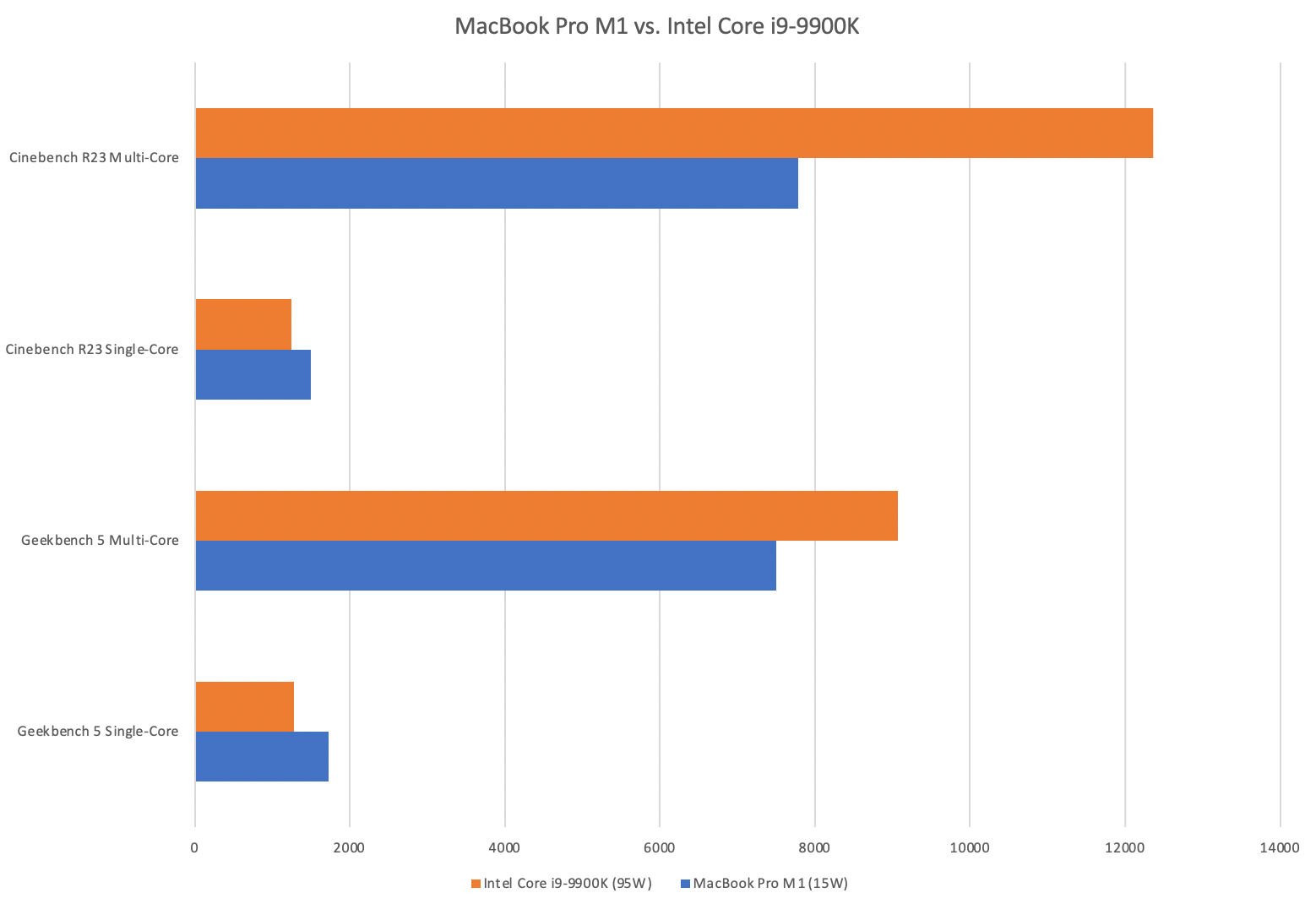

But then, some significant Geekbench scores started popping up, followed by Cinebench R23 scores showing the M1 outperforming 95W desktop processors.

Thus, I celebrated the arrival of my M1 MacBook Pro a couple of days ago with great pomp and celebration on Twitter:

My Apple Silicon M1 MacBook is here but I CAN’T UNBOX IT BECAUSE I HAVE WORK COMMITMENTS THAT I AM ALREADY BEHIND ON SO I AM GOING TO BE A RESPONSIBLE ADULT AND FINISH THIS WEEK’S WORK FIRST. pic.twitter.com/lcBhMcHmRp

— Nadim Kobeissi (@kaepora) November 26, 2020

I even posted absurd videos of me unboxing the MacBook to sensuous music, which I thought was pretty funny. But really, given what I had been reading about the chip, I was very excited to see for myself whether all the claims were true.

But which claims are those, exactly? Well:

- Unreal performance for a 15W CPU: Geekbench shows the Apple M1 beating every Mac ever made in single-core performance, and scoring right below a freaking Intel Xeon W-2140B on multi-core performance, as shown above.

- Huge battery life gains on same-size batteries: Apple promised roughly double the battery life on the MacBook Pro without any hardware changes whatsoever other than the replacement of the Intel chip with an M1 chip.

- Non-existent thermal throttling, fan noise or heat output: The MacBook Air doesn’t even have a fan anymore.

At the risk of making this a very boring review, all I have to say is basically that all of the above is so far holding as true. This computer is nuts. Compiling tons of things in the background doesn’t slow down Safari web browsing, somehow. I haven’t had to plug it in once since I fully charged it up two days ago. Performance is so quiet and cool that I feel like my terminal compiling a bunch of things is actually an SSH into a much stronger workstation located somewhere else. I actually discovered that I’ve had an instinct of measuring my MacBook’s CPU usage by feeling the heat on the strip of aluminum right above the Touch Bar, and I can’t even do that anymore now. Because even if the M1 MacBook Pro has been running at 100% on all cores for ten straight minutes, you’ll barely feel it getting warm.

This just doesn’t feel like an entry-level 13” laptop. It feels like a workstation that’s magically bottled within a 13” laptop chassis.

Differences with the M1 MacBook Air: Not Just Active Cooling

Many reviews and articles online are stating that the only difference between the M1 MacBook Pro and the M1 MacBook Air is “the fan”, i.e. the fact that the MacBook Pro has an active cooling solution that allows it to sustain high performance for an extended period of time without succumbing to thermal throttling. Generally speaking, the MacBook Air doesn’t seem to exhibit thermals-induced throttling until around 10 minutes of sustained load, which is miles away from the mere seconds it takes Intel processors to start clocking down cores.

However, it’s seriously inaccurate to say that active cooling is the only difference, and I want to list all differences I am aware of (in order of personal relevance) aside from the active cooling solution:

- Battery Life: The MacBook Pro is equipped with a larger battery, giving it an average of two hours longer battery life in most involved workloads.

- Number of GPU Cores: The base model MacBook Air comes with 7 GPU cores instead of 8, with the rest of the M1 chip appearing to be identical. This is likely the result of binning. You’ll have to shell an extra ~$250 for a model with a comparable, non-binned M1 chip to the MacBook Pro, and that will net you an upgraded 512GB SSD as well.

- Display Brightness: The Pro and the Air have displays with the exact same quality metrics, color gamut/accuracy, viewing angles and so on. The only difference is that the MacBook Pro offers 100 extra nits of brightness, capping it at 500 nits, whereas the MacBook Air is limited to 400 nits. It’s important to note that the previous, non-M1 MacBook Air’s display was not as comparable to the Pro line, lacking, for example, a P3 color gamut. So this year’s Air display is markedly better, brightness improvements aside.

- Speaker Quality: The Pro line is equipped with speakers that offer slightly superior audio quality, thanks to a broader dynamic range.

- Microphone Quality: Macbook Pros have significantly superior microphones. Unlike the speaker quality, the difference here is significant and easy to pick up on.

- Touch Bar: The MacBook Pro has a Touch Bar. I’ve never had a strong opinion on the Touch Bar. I don’t think it matters whether it’s there or not so long as MacBooks have a physical escape key, which Apple thankfully brought back to the Pro line in late 2019.

- Chassis Thickness: Somewhat counter-intuitively, the Pro is actually thinner than the Air, but not by much, and I don’t think this matters at all. The Air is also lighter but to a degree that’s equally insignificant.

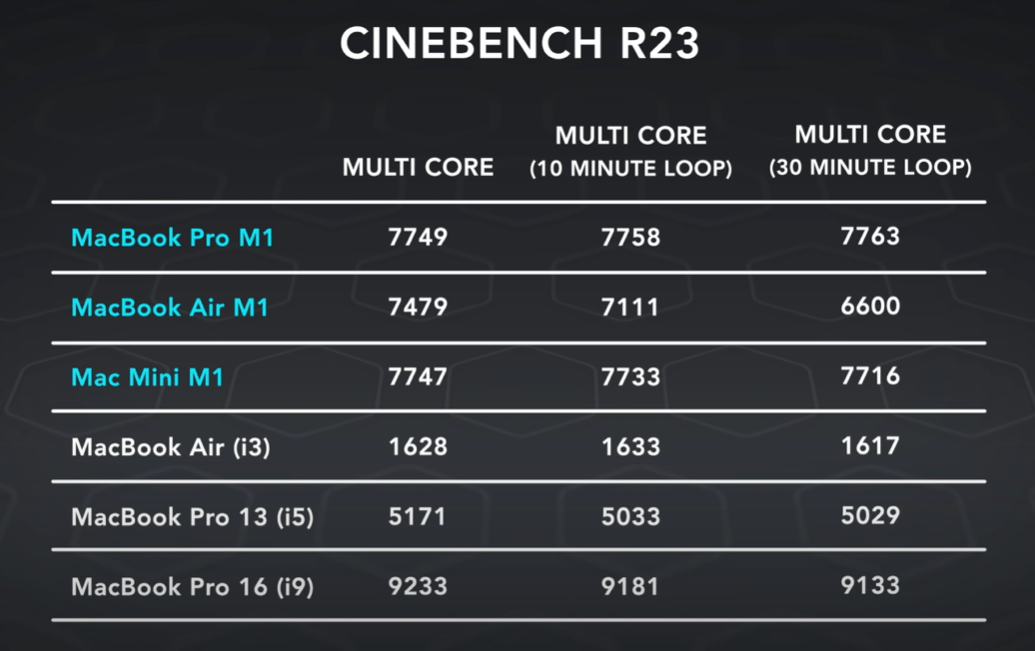

Aside from that, the fan alone is actually already a pretty big difference. Dave Lee, one of my favorite tech YouTubers, published a great video on the M1 Macs in which he provided a Cinebench R23 comparison that illustrates a serious difference in sustained, multi-core performance between the MacBook Pro and the MacBook Air which is almost certainly entirely due to the active cooling solution:

After 30 minutes of sustained mutli-core work, the performance dropped 15% on the MacBook Air compared to the Pro.

Active cooling is critically important to me because of my work on developing and testing Verifpal, cryptographic protocol modeling and analysis software that runs analyses which can easily fill a handful of CPU cores for an hour or longer. But scientific work aside, it does feel to me like the non-handicapped M1 chip, longer battery life, and peppering of quality of life improvements in the form of display, speaker and microphone improvements do justify the $300 price premium.

To me, understanding these differences between the Air and the Pro felt important because if I were to spring for the Pro, that’s a $300 difference that I wanted to justify to myself. Other reviews should mention all these differences more clearly in order to allow readers to make a more informed decision. I am personally not aware of any other difference between the M1 Air and Pro computers and think that’s all there is to it.

On Sticking to the Base Model: 8GB RAM, 256GB SSD

I personally don’t need more than 256GB of storage on my work computer and so settling for that isn’t at all an issue for me. The RAM was a more difficult question. However, given that this M1 was a completely unnecessary purchase (I have a very capable laptop that I bought only ten months ago), I wanted to see whether I could survive on the base model with 8GB RAM. I was encouraged to give this configuration a shot by the many articles and videos out there which argued that somehow, magically, 8GB of RAM performed better on M1 than it does on Intel Macs.

From my own experience, I so far am not sure that I agree that 8GB of RAM is enough for most developers. I’m happy with it so far; my most hardcore development scenario involved Visual Studio Code open along with a single terminal for compiling, debugging and testing, so I’m fine. However even with that, I seem to be constantly occupying the vast majority of my RAM, and things can get too close for comfort. Add a dozen browser tabs and a couple of Rosetta-translated apps and that’s it, you’re redlining in terms of memory pressure. I don’t know if that’s okay, and it’s not what I would expect from a “Pro” laptop. I think that while it’s true that 8GB of RAM does perform better on M1 than on Intel, claims of this being automagically sufficient for “95% of users” are a bit bogus. That being said, I’m satisfied with my 8GB of RAM. I think Apple should consider shipping 12GB RAM base models next year, however, if only on the 13” Pros. This would strike a needed sweet spot.

Update (July 8th, 2021): I am no longer satisfied with my 8GB of RAM and wish that I got the 16GB model. I’m frequently caching to disk when having a bunch of browser tabs open and doing development work, especially with XCode and Simulator. I’ll be getting a 16GB RAM MacBook (with a 512GB SSD to handle those big Xcode Simulator images and build caches, among other things) when I upgrade.

Quality of Life: Daily Use, Reliability, Battery Life

Everything is fast. Opening websites is fast, partly due to Wi-Fi 6 but also partly due to insanely fast render times in Safari. Sleep and wakeup are iPhone levels of fast. Changing screen resolutions happens instantly and without that fade-to-black ritual which has been the rule for the past two decades.

There is absolutely no thermal throttling that I’ve witnessed on my MacBook Pro. This alone has nutty implications for any kind of heavy laptop-based workloads. Benchmarks across the Internet are indicating that the M1 MacBook Air is trouncing the 16” MacBook Pro on Final Cut Pro render times, Xcode compilation times and virtually any other similarly heavy task.

There are also some pretty fascinating things to take into account: Rosetta-translated apps seem to run faster on M1 than on Intel in most cases. I don’t know how that’s true, but it is.

Overall there’s nothing more to say here about general quality of life on this machine. Rosetta is so smooth and fast that you don’t even notice you’re running emulated apps. Apple knew how important this would be to the success of rolling a new architecture towards a base of people who, of course, are in majority not computer nerds who even care which instruction set their new laptop runs on.

The M1 seems to be restricted in terms of PCI Express lanes and this manifests in all M1 Macs (even desktop Macs) being restricted to only two Thunderbolt 4 ports. This is a problem. Two ports aren’t enough on a Pro machine.

I ran Geekbench 5 and Cinebench R23 on my M1 MacBook Pro, a tiny laptop with a 15-watt CPU, and on my Intel Core i9-9900K workstation, a 95-watt behemoth:

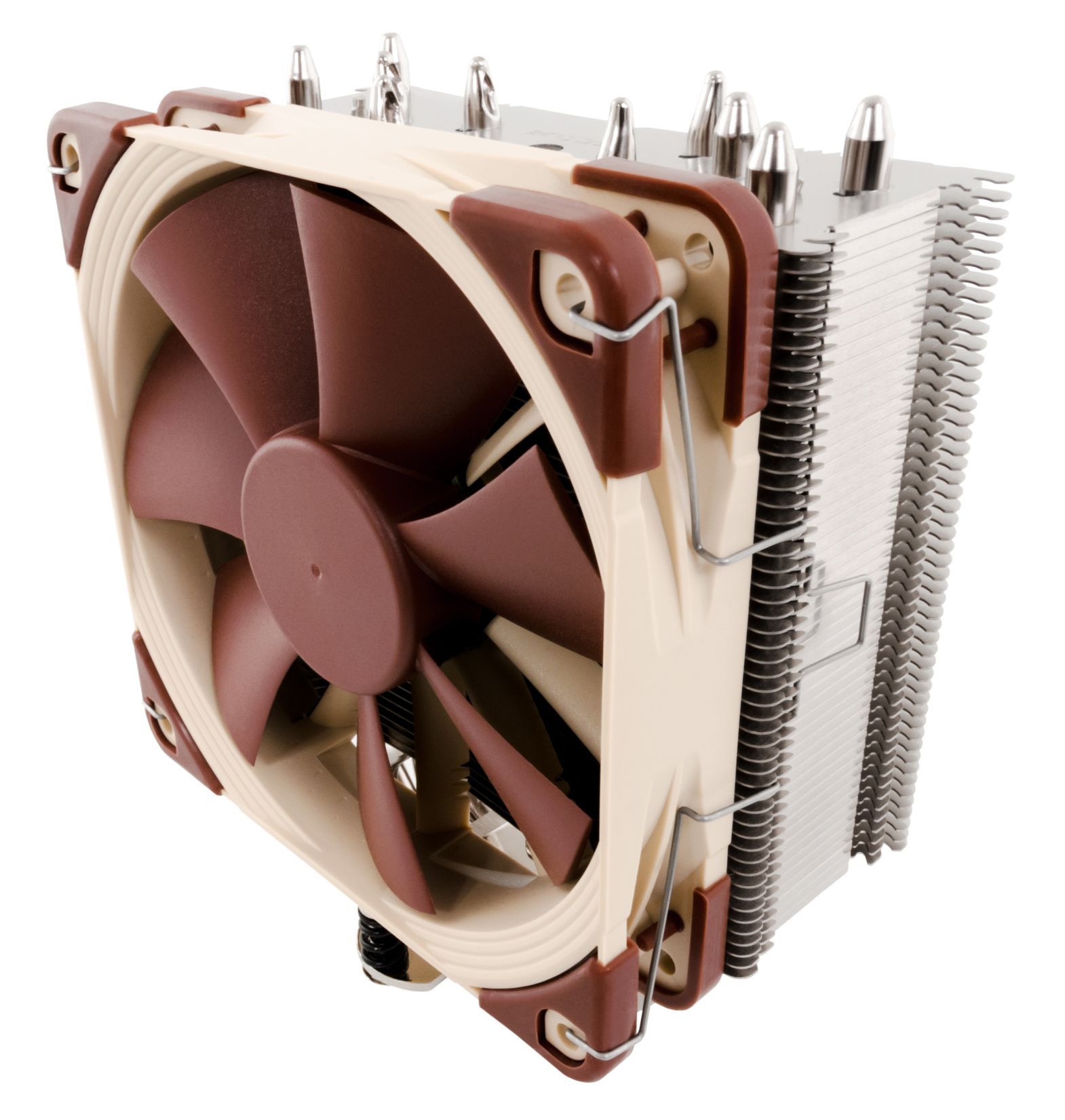

I think it’s important to be clear that this is what the Core i9-9900K requires to stay cool, and that it’s barely enough despite making the sound of a jet engine:

Developing on the Apple Silicon M1

First, the good news: Xcode is silly fast, Rust just released (hours ago) support for Apple M1 in the beta branch of rustup, Visual Studio Code’s “Exploration” beta runs natively on M1, and Rosetta is great for everything else, including installing and running the entire Go toolchain compiled for Intel.

The bad news:

- Homebrew isn’t ready and this single-handedly makes development on M1 a bad experience. Homebrew for ARM exists and it works fine. You can install it, add it to your

PATHand install by calling down formulas. Then, half of the formulas don’t compile, and nobody has bottles up yet. I wasn’t able to installneovim,ffmpegandgpgthrough Homebrew. I was however able to installfish,aria2,tmux,htop, and some other stuff. And I got a precompiledneovimIntel binary to run great through Rosetta (and I’m using it to write this post!). I was later able to compileneovimmyself and just run it natively. - Go won’t officially support Apple Silicon binary compilation until February 2021. This is pretty slow especially compared to Rust. Apple’s been giving out dev kits since June.

Once Homebrew for ARM has matured and is reliable, developing on the M1 should be a breeze. I don’t suspect this will take too long as many kind and talented engineers are working hard on making it happen.

Conclusion

I love what Apple is doing here. I’m selling all my other computers. This is the computing experience I’ve been waiting for my whole life, and I’m satisfied. Suggestions for future improvement, drawn largely from this article:

- Increase the RAM configuration to 12GB on the base model.

- Increase the PCIe lanes such that four Thunderbolt 4 ports are possible on 13” models.

I have no other requests. I love my M1. I have no idea how Intel and the Windows ecosystem are going to catch up to this.